Launch the Next Great Pilot

12.16.15 · Ashley Bowen Cook

Never underestimate your power to influence. As the aviation industry struggles to encourage more people to consider the left seat as a professional power position, we’d be wise to consider the lessons learned by those who’ve built illustrious careers that soar well above the ground. The December Wichita Aero Club “Great Pilots” panel, moderated by my father, aviation photographer Paul Bowen, provided a platform for storytelling – a sharing of passion, talent, networking and friendships. And it showed how one generation influences the next.

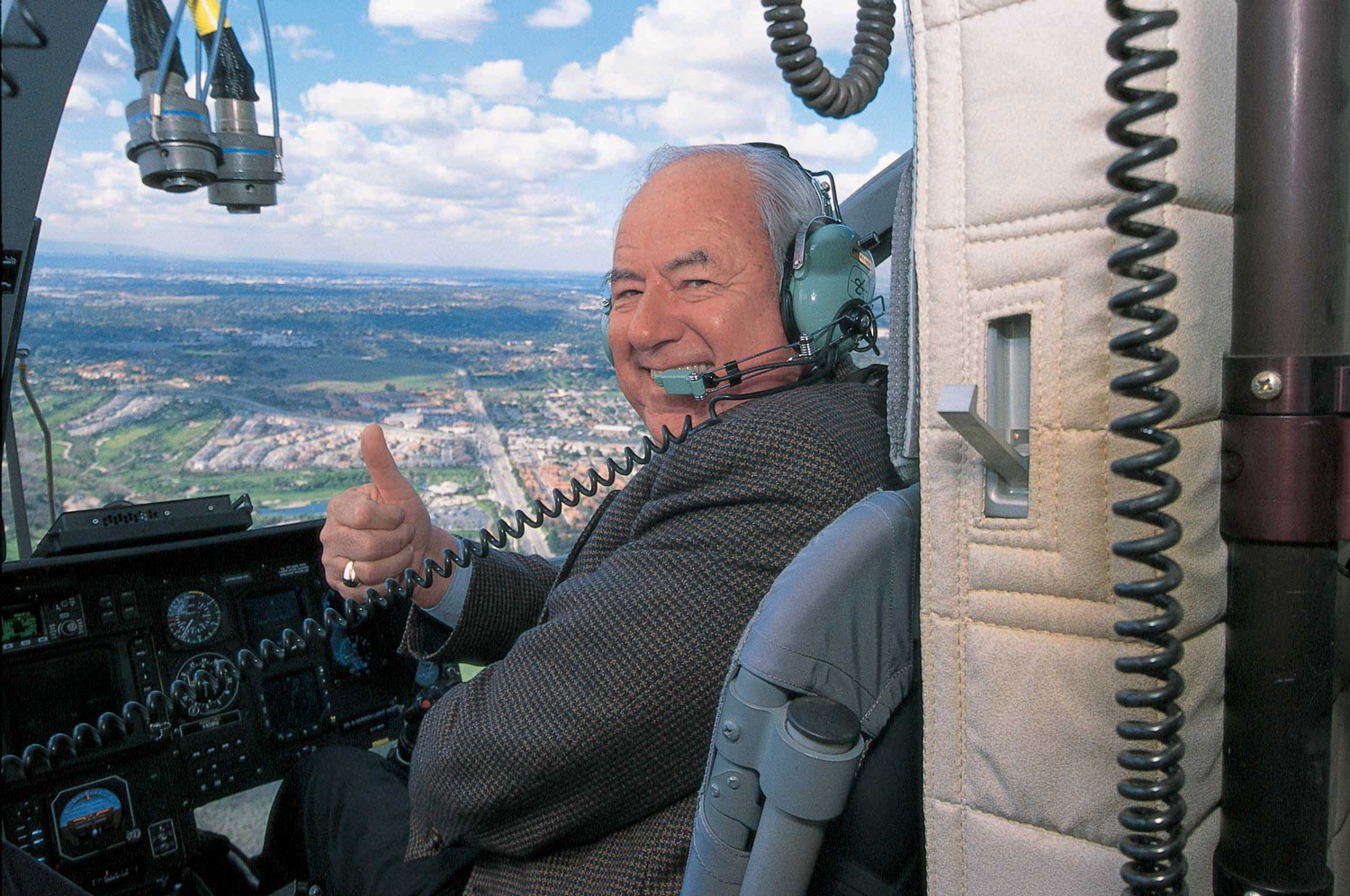

Veteran aviator Clay Lacy benefited from a grandmother who let Orville Sanders build an airport on her farm. His mom would take the young Clay to watch takeoffs and landings. He was flying at age 12. “Sanders was kind of a loose guy,” said Lacy, “which was good for me. He’d let me fly anything.” By age 19, Lacy snagged a job as copilot with United. He later sold jets for Bill Lear, then revolutionized air-to-air filming for the movie industry. Lacy quit logging flight hours when they exceeded 50,000. He’s been flying for seven decades.

Legendary P-51 pilot Lee Lauderback, whose father was a Navy pilot, followed close behind. “I started flying late – at the age of 14,” deadpanned Lauderback, who started with gliders and soloed in a Cessna 150 on his 16th birthday. “I hocked everything I had to buy my first sailplane,” he said. He went on to become corporate pilot for Arnold Palmer and log more than 21,000 flight hours, with 9,000 of those in his beloved P-51 Mustang – which he also uses to provide upset training.

Angela West, who gamely stood in for a flu-stricken Patty Wagstaff, said she became fascinated with aviation while in school. When she told her parents, who had never been around planes, “They were like, ‘Yeah, right.’” Once West took her first ride in a Cessna, she knew her career would involve flying. Somehow. Some way. Like her parents, her friends also didn’t get the attraction. A friend asked, “Are you running drugs or what?” West went on to become a pilot and to manage corporate events for Kermit Weeks at his renowned Fantasy of Flight in Polk City, Florida.

Each took very different career paths. Recounting those would fill books. Speaking of which, you can read Lacy’s – Lucky Me – online. He’s quick to say that it’s not an autobiography: “Other people wrote the majority of it.” But then he adds, “I like it.” The man who became Mr. Learjet in 1964 sure has the stories to tell. The Next Generation: Pay It Forward

Lauderback noted that aviation is a more expensive and complex field to enter than it used to be. His advice to young aviators: “Don’t give up. Keep cracking the door open until some sunshine comes in.” He also acknowledged the influence Clay Lacy had on him. Lacy owns a purple P-51 Mustang, which he flew in the Reno Air Races. When Lauderback was a kid, he purchased a P-51 model and painted it to match Lacy’s aircraft. We all need role models. Including ones flying purple planes.

During this season of giving, consider how you can donate time, talent or treasure in making a difference for an aspiring aviator. Take the time to speak with students. Let them sit in the cockpit of your aircraft. Give money toward a scholarship. You could be inspiring the next Lee Lauderback, Clay Lacy or Angela West.

This column ran in the December 17 issue of Bluesky Business Aviation News.