B-29 Superfortress Doc Comes Home

06.14.18 · Greteman Group

By Deanna Harms, executive vice president, at Greteman Group, a marketing communications agency in Wichita, the Air Capital.

I last shared news of Doc, one of only two fully restored, flying B-29 Superfortress bombers, back in 2015. I have an update for you. Volunteers Josh Wells and Franklin Berry were on hand at the June meeting of the Wichita Aero Club to catch us up to speed.

Doc will have a new home this fall. Construction of a 30,000-square-foot, $6.6 million hangar on the Wichita Eisenhower National Airport campus began this April. Structural steel is going up now. Plans call for Doc to arrive at the hangar site in mid-October, with construction complete in November. The facility will be a mix of working hangar (where you can watch the plane being serviced), STEM education (the Cosmosphere is helping write the science, technology, engineering and mathematics-based curriculum), and eye-opening aviation museum.

More Than an Aircraft – A Sacred Bond

How is it that we feel so connected to some aircraft? The B-29 Superfortress known as Doc doesn’t just elicit curiosity. It’s a showstopper. People flock to it. They stand in line for hours, if needed, to board this break-the-mold aircraft. And some choke back tears.

Like 93-year-old Jerome Micka who flew 29 B-29 missions during WWII, with his last one dropping supplies to U.S. prisoners of war. Owen Hughes, the 99-year-old artist who painted the plane’s original nose art. Hughes served in the European theater in WWII as a sign painter. In early June, he got to ride on Doc – the first time he’d ever been on a B-29. We preserve history for many reasons. But to honor those who made that history is probably the best reason of all.

A Long Climb Back

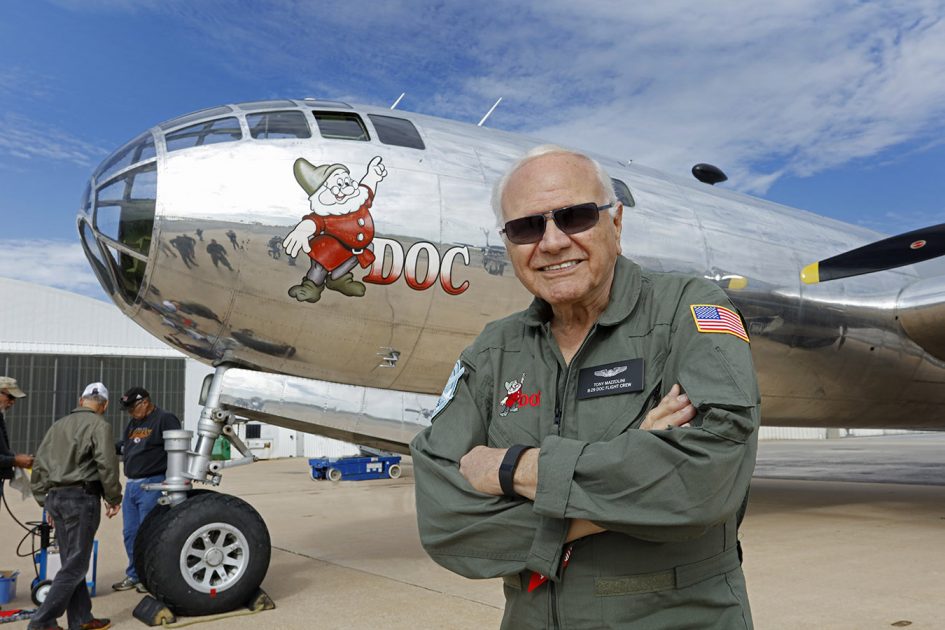

Doc was part of an nine-aircraft squadron named for Snow White, the Seven Dwarfs and the Wicked Witch. It was among the 1,644 B-29s built in Kansas during World War II. While Doc, built in 1945 toward the war’s conclusion, never saw combat, it survived 42 years sitting in a California Mojave desert target range. In 2000, owner Tony Mazzolini brought Doc to Wichita after talking to Jeff Turner, then Boeing Wichita general manager and later Spirit AeroSystems CEO. “Jeff said, ‘If you can get it to Wichita, we’ll get it put back together,” Wells recounted. The plane was in so many pieces, people coming to see the aircraft would laugh as they left, not believing the volunteers could ever get the puzzle back together.

In 2013, aviation enthusiasts and business leaders led by the then-retired Jeff Turner formed the nonprofit Doc’s Friends. They went to work generating the resources needed to make magic. Through the years, hundreds of skilled workers and retirees from Boeing and Spirit AeroSystems, veterans and others have volunteered more than 300,000 hours on Doc’s restoration.

A Three-Stage Plan of Attack

Wells outlined Doc’s trajectory in three phases. One, raise money to restore the plane and get Doc flying. Two, operate it as a flying museum. Three, find a permanent home.

In 2016, Doc flew for the first time in 60 years. This past year, this fully restored, flying B-29 bomber (one of only two in the world) attended eight airshows and special events. Its first was AirVenture in Oshkosh last July. Doc just returned from a 5.5-hour flight to Reading, PA. Franklin Berry, who serves as a flight engineer on Doc, reported there were no squawks, that the aircraft “flies flawlessly.”

During peak wartime production, Boeing Wichita produced four and a half B-29s a day. Compare that, Wells said to Spirit AeroSystem’s current production rate of two fuselages a day that get shipped out on rail for completion elsewhere. Those early B-29s flew out of Wichita. Doc is one of only two B-29s restored to flying condition. The Commemorative Air Force has the other, Fifi, based in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. There are only eight left-seat certified pilots for both Doc and Fifi, so they draw upon the same crew.

Innovation in Flight

Many see the B-29 bomber as a tool that helped end a global war that led to the deaths of more than 50 million people. It dropped the world’s first atomic bombs. The Enola Gay bombed Hiroshima on August 6. Bockscar hit Nagasaki on August 9. Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945.

How did the B-29 play such a pivotal role? Flying up to 350 mph at more than 30,000 feet, the B-29 could fly faster and higher than most interceptor aircraft. It extended the range to 4,000 miles and the payload to 20,000 pounds. It was the first pressurized, all-electric, long-range bomber. The B-29’s advanced-for-the-times technology makes Doc an excellent flying classroom, educating and connecting with audiences young and old.

In spite of these advances, Wells said the wartime B-29s that were churned out were relatively unsafe and built to be expendable. He said more pilots were lost to mechanical failure than to enemy fire. “The engines were trying to kill you,” he said. Doc’s restoration, though, was just the opposite. It was done with longevity in mind. They plan to fly Doc another 30 or 40 years.

Fueling History

The goal is for Doc to pay its own way. Doc burns about $3,000 of fuel a flight hour so a recent four-day trip took about $28,000 just for the gas. “We go to airshows to make money,” Wells said. You can check out Doc’s schedule here, including its participation once again in EAA AirVenture, July 23-29. “We want to be the bomber of choice for airshows,” Wells said.

You Can Go Home Again

This iconic aircraft has returned to its birthplace and will soon have a home deserving of its place in history. Doc’s Friends are hard at work raising the remaining $1 million or so needed to fund Doc’s new home. Wells said the project is both on schedule and on budget. To learn more about Doc or to donate, please go to B-29Doc.com/Donate.

This column originally appeared in the June 14, 2018 issue of BlueSky News.